Saturday, February 28, 2009

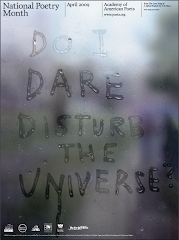

Why We Read?

http://citypaper.com/special/story.asp?id=16743

It's an article about loving books, and why the books we read when we're younger "May Be The Most Important Reading We Ever Do." Enjoy!

Friday, February 27, 2009

Just for Fun!

Does number 12 look familiar? The other buildings are amazing too!

Thursday, February 26, 2009

The Hours! (aka: Michael Cunningham is a genius)

While reading Michael Cunningham, keep your eye out for subtle references to VW and Mrs. D. They litter every page, for sure. Some are not so subtle... like Clarissa Vaughn's nickname... but check out the names of the other characters. Most main characters have names we encountered in Mrs. D, but many are used for people who play a different role. Also, it's neat to observe how MC has changed the Sally/Clarissa story. And don't forget Mary Krull... you'll meet her later. And what does Wellfleet remind us of? Bourton? NO WAY!

Another thing that impresses me all the time about The Hours is MC's ability to create for us VW's mental state (and Mrs. Brown's, for that matter). His descriptions of diseased mental health are spot-on and very realistic. I am 100% convinced while reading this book that MC actually has lived inside VW's brain... he's that good.

This is one well-crafted novel, I'd say. But who am I to say? What do YOU say?!

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Updated Page Numbers for Window References

Here are the page numbers for the window references in Mrs. Dalloway for the version all of you have. See my other blogs for my own two cents for some of the passages. Hope you're enjoying The Hours!

3, 5, 9, 13, 14, 15, 24, 30, 31, 37, 47, 48, 53, 54, 61, 88, 89, 112, 113, 126, 127, 134, 138, 149, 150, 163, 168, 184, 185, 186

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Flowers in Mrs. Dalloway

Regent's Park was mentioned numerous times, and I included those examples with my flower references because I felt that they encompassed flowers and gardens and plant-life as a whole, a theme Woolf really delves into in the text. Regent's Park becomes a place where all the characters mentioned wander, either physically or mentally, and have some memory or experience there.

ROSE is mentioned perhaps more than any other flower. This is used to describe women of beauty, particularly Sally and Elizabeth, in the eyes of Mrs. Dalloway and her husband, in terms of his daughter. The word "rose" is also played with when used as a verb rather than describing a literal flower, as is the word "flower" used to also describe the emergence of people and ideas, such as, "It has flowered; flowered from vanity, ambition, idealism, passion, loneliness, courage, laziness, the usual seeds..." (page 84). When discussing time passing, weeds is mentioned (along with waves!).

"But she deared time itself, and read on Lady Bruton's face, as if it had been a dial cut in impassive stone, the dwindling of life; how year by year her share was sliced; how little the margin that remained was capable any longer of stretching, of absorbing, asin the youthful years, the colours, salts, tones of existence, so that she filled the room she entered, and felt often as she stood hesitating one moment on the threshold of her drawing-room, an exqisite suspense, such as might stay a digver before plunging while the sea darkens and brightens beneath him, and the wabes which threaten to break, but only gently split their surface roll and conceal and encrust as they just turn over the weeds with pearl." (page 30, DEFINITELY a PERIOD SENTENCE).

I thought it important to mention this along with the observance of flowers, because when people are compared with flowers in Mrs. Dalloway, they are always youthful and beautiful (Elizabeth and Sally in Clarissa's memory of her as a girl), and the view on time and age is played with throughout the novel. Growing older is generally unfavored among the different characters, and I think the inclusion of "weeds" within the sadness and helplessness of time really acknowledges this. I also thought it interesting that Clarissa remarks at one point that at fifty-two, she did not feel old yet, while Peter thought that made her quite old.

I also noted the mention of Mrs. Dalloway's "green dress" seemed to pop up quite often as well, and there were a fair share Shakespeare references. Religion played a part in the novel as well, and it was interesting to see the division between instituionalized religion and God, Nature verus Divinity, and human nature. Clarissa seems to revel in the concept of God, by shy away from what others consider to be sins, and also deeply analyzes her memories and feelings for Sally and the difference to her between a love for a man and love for a woman.

Birds, birds, birds

At the start of the book, Clarissa is described as bird-like and beak-faced. She is also described, as Megan pointed out, as cutting people into pieces. The beak-face and the sharpness seem to go hand in hand, to me (I'm imagining a bird pecking things to bits). I think that perhaps this sharpness, and coldness, may be a form of defense for Clarissa. She thinks, in the novel, about how dangerous it is to live for even just one day (and Septimus is proof of this thought), which suggests to me that there is a good deal of fear inside Clarissa. Perhaps her sharpness and her quickness and her coldness are her methods for protecting herself from this danger.

At the end of the novel, when Septimus jumps from his window to escape the doctor, Lucrezia blocks the stairwell in order not to let the doctor pass. Septimus imagines her as hen-like, with arms out at her sides like wings to block the way. She protects him, defends him, as a bird. This seems like a parallel between Septimus and Clarissa (shock and surprise) who both appear to use birds and bird-like behavior as methods to defend themselves from the intrusive outside world.

Monday, February 23, 2009

Birds in Mrs. Dalloway

Because there were so many references to birds, I decided to only note the passages in which birds were deliberately mentioned or a character was described as bird-like.

Page 4 - Clarissa as a jay

Page 10- Clarissa's face being described as "beaked"

Page 14 - Septimus is "beak-nosed"

Page 35 - Sally as a flying bird

Page 43 - Clarissa as a "fluttering" bird

Page 56 -Peter sinking into the "plumes and feathers of sleep"

Page 82 - Septimus watching Lucrezia "as one watches a bird"

Page 102 - Sir William as a bird of prey

Page 145 - The screen in Septimus' room with birds on it

Page 146 - Septimus being described as a young hawk

Page 147 - Lucrezia's mind falling from branch to branch, like a bird

Page 148 - I'm a little confused - is Lucrezia referring to Septimus or Sir William Bradshaw?

Page 149 - Lucrezia as a "little hen"

Page 153 - Sally as a goose....a silly goose?

Page 162 - Miss Parry as a bird frozen to it's perch

Page 164 - Peter with hawk-like eyes

Page 168 - Clarissa's curtain with the birds of Paradise on it

Page 170 - Clarissa's curtain, again

There's so much that can be deducted from Woolf's constant bird-like descriptions of the various characters. While I still stick by my original idea of Clarissa and Septimus (and Lucrezia) being trapped in "bird cages" by their lives and society, I've also become more interested in how Woolf differentiates between males and females by using bird-like descriptions.

Many of the males, especially Septimus, are described as hawk-like or having qualities similar to those of a raptor.

The women, on the other hand, are described in a more delicate fashion. They are jays, hens, and fluttering birds.

I have seen this theme of men as raptors and females as delicate songbirds in other pieces of literature, and was interested to see that Woolf used this symbolism so deliberately in Mrs. Dalloway.

" Buds on the Tree of Life"

“It was her life, and bending her head over the hall table, she bowed beneath the influence, felt blessed and purified, saying to herself, as she took the pad with the telephone message on it, how many moments like this are buds on the tree of life, flowers of darkness they are, she thought (as if some lovely rose had blossomed for her eyes only)….” (pg. 29)

Also seen (12, 15,22, 23, 29, 76, 83, 98, 121, 134, 154)

An Escape

"Getting up rather unsteadily, hopping indeed from foot to foot, [Septimus] considered Mrs. Filmer's nice clean bread-knife with 'Bread' carved on the handle. Ah, but one mustn't spoil that. The gas fire? But it was too late now. Holmes was coming. Razors he might have got, but Rezia, who always did that sort of thing, had packed them. There remained only the window, the large Bloomsbury lodging-house window; the tiresome, the troublesome, and rather melodramatic business of opening the window and throwing himself out. It was their idea of tragedy, not his or Rezia's (for she was with him). But he would wait till the very last moment. He did not want to die. Life was good. The sun hot. Only human beings? Coming down the staircase opposite an old man stopped and stared at him. Holmes was at the door. 'I'll give it you!' he cried, and flung himself vigorously, violently down on to Mrs. Filmer's area railings." (108, some page much later in the newer editions)

Though not to that extremity, Clarissa uses a window as a way of escape from her party after hearing about Septimus, and shares the moment with observing the outside world and others as he did in his last moments.

"[Clarissa] walked to the window. It held, foolish as the idea was, something of her own in it, this country sky, this sky above Westminster. She parted the curtains, she looked. Oh, but how surprising! -- in the room opposite the old lady stared straight at her! She was going to bed. And the sky. It will be a solemn sky, she had thought, it will be a dusky sky, turning away its cheek in beauty... She was going to bed, in the room opposite. It was fascinating to watch her, moving about, that old lady, crossing the room, coming to the window. Could she see her? It was fascinating, with people still laughing and shouting in the drawing-room, to watch that old woman, quite quietly, going to bed alone. She pulled the blind now. The clock began striking. The young man had killed himself; but she did not pity him; with the clock striking the hour, one, two, three, she did not pity him, with all this going on. There! the old lady had put out her light! the whole house was dark now with this going on... She must go back to them. But what an extraordinary night! She felt somehow very like him -- the young man who had killed himself. She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away while they went on living. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. But she must go back. She must assemble. She must find Sally and Peter. And she came in from the little room." (134-5, fairly close to the end)

Saturday, February 21, 2009

The Pocketknife and Other References to Knives

pg.8 ("She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on...)

pg. 40 (Peter opens the pocket knife halfway)

pg. 41 (Clarissa takes notice of his fidgeting with the knife)

pg. 44 (The knife makes Clarissa feel self-conscious)

pg. 46 (Clarissa gets annoyed with Peter for continuing to toy with the knife)

pg. 71 ("Every woman, even the most respectable, had roses blooming under glass; lips cut with a knife..."

pg. 80 (Peter pulls out his pocketknife again as he thinks about Daisy meeting with Major Orde, and his jealousy is apparent)

pg. 92 ("Food was pleasant; the sun hot; and his killing oneself, how does one set about it, with a table knife...")

pg. 104 ("She had never seen the sense of cutting people up, as Clarissa Dalloway did, cutting them up and sticking them together again..."

pg. 119 (Clarissa recalls an image of Peter playing with the knife "just like he always does")

pg. 147 (Rezia thinks of knives and forks when she is bringing Septimus his letters)

pg. 149 ("Getting up rather unsteadily, hopping indeed from foot to foot, he considered Mrs. Filmer's nice clean bread knife with 'Bread' carved on the handle")

pg. 157 (Peter empties his pockets at the hotel and his pocketknife is removed)

pg. 159 (Peter is sure to grab his pocketknife before he departs for the party)

pg. 165 (Peter opens the blade before entering Clarissa's house)

pg. 187 (Sally takes notice of Peter's "old trick" of fidgeting with the pocketknife when he gets excited and anxious)

pg. 192 (Peter continues to fidget with the device as he thinks about Clarissa)

I am still under the opinion that the pocketknife is symbolic of Peter's pain regarding Clarissa's rejection. Clarissa is described as being able to "slice like a knife through every thing," and this implies that she does not necessarily take people's feelings into account. She moves and makes decisions without caution at times. Lady Bruton also describes Clarissa as someone who cuts people up and tries to put them back together. The knife cannot simply be a device that Peter uses when he needs to fidget. It could have been any object. A marble? A pocket watch?

-Megan R.

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Periodic sentence in Mrs. Dalloway?

page 6

Septimus & Clarissa - Birds in a cage?

I had decided to follow the theme of birds in the text, and found that the first hints at the relation between Clarissa and Septimus is subtly pointed out in their physical descriptions; both characters are described as bird-like.

When Clarissa is heading out to buy flowers, Scrope Purvis notes that she is "perched" on the side of the road, and has "a touch of the bird about her, of the jay, blue-green, light, vivacious," (4).

Septimus is not described as a bird in such detail as Clarissa, but his brief physical description on page 14 notes that he is "beak-nosed."

The reader slowly begins to discover that these characters feel unhappy with and trapped in their everyday lives (Septimus more obviously so). Perhaps their bird-like descriptions metaphorically represent their desire to fly away? Or maybe these descriptions are meant to hint that Septimus and Clarissa are trapped, like pet birds, in the cage of society?

I have no doubts that Woolf described these characters as bird-like on purpose, and am interested to see how if the theme continues through the rest of the novel.

In The Ashes of a Cigarette

Looking Through the Glass

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

I'm Not Afraid of Virginia Woolf, but I Might Be Afraid of Peter's Pocketknife

So what is this reoccurring image all about?

I think that the knife has a few different purposes in the text. First and foremost, it represents Clarissa stabbing Peter in the back, so to speak. She chose to marry Mr. Dalloway, who seems to be an awful match for her instead of Peter. When Clarissa sees the knife, she is reminded of her mistake. That is why the combination of the knife and Peter's tears create a surge of emotion in Clarissa who ends up kissing him. The knife is also Peter's reminder that he is up against some tough weapons in cracking Clarissa, including Clarissa herself. He is still in love with her and must work toward her love as well. The knife, of course, is a symbol of masculinity as well. Peter's toying with the knife gives Clarissa a trivial reason to dislike Peter, and that's what Clarissa needs is a multitude of reasons to convince herself that she made the right choice with Mr. Dalloway.

-Megan R.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

is this metaphor too much?

some backdated stuff . . . sorry i'm playing a bit of catch up

Like-minded teacher, Gloria Watkins expresses similar views with a feminist twist in her essay, Toward a Revolutionary Feminist Pedagogy. She suggests, in order to create more transformative education experiences, our professors “should engage students in a learning process that makes the world ‘more rather than less real’” (Watkins 81). In order to achieve this subjective knowledge through teaching, “We must be willing to deconstruct this power dimension, to challenge, change, and create new approaches” (Watkins 84).

150 word comparison of freire and hooks

and it totally is . . . without the in-text citations. because then its 162 words.

if we're counting. and we most certainly are.

Monday, February 16, 2009

Mrs. Dalloway!!

"Make it new!" - the mantra of Ezra Pound, and a slogan that serves as a decent representation of Modernist ideals.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Viswanathan's Idea of Mind Control Through Literature

"The English literary text, functioning as a surrogate Englishman in his highest and most perfect state, becomes a mask of economic exploitation, so successfully camouflaging the material activities of the colonizer..." (67).

I found Gauri Viswanathan's theory on the development of English studies as a discipline extremely thought-provoking, especially because America was obviously once a colony of Britain, the same country that exploited India by use of literature for ages. I have always viewed reading as an action that symbolizes freedom. I have a choice regarding what I read, who I read, and how I read a given text. Viswanathan, who was born in Calcutta, India, believes that studying English literature is a symbol of control, the exact opposite of my own thinking. I completely understand where she is coming from on the topic seeing as she is Indian-born, and has witnessed her own reasoning in her day-to-day life.

The Indian people read English literature to make themselves feel as if they were assimilating into a culture that was superior to their own. They read to gain dignity in the eyes of their colonizers who viewed them as incomplete, inferior, and imperfect human beings. In reading what the English threw in front of them, the Indian people were allowing colonization of the mind to occur.

Viswanathan points out that English programs in American schools sprouted up after colonization had been ended in the states, following the Revolutionary War. Why do you think American schools would establish these programs after the English had already liberated the colonies? The programs were clearly not a means of control and colonization, so why did English become such a vital course of study in American classrooms?

-Megan R.

A paper-writing tool...

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/

This is a guide for paper formatting (including citations and reference lists) for MLA and APA styles. The site for MLA is here: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/557/01/.

It's a fantastic site that has just about everything you could possibly need to properly cite sources and properly format your papers. I use it every time I write a paper, literally. It's wonderful.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

From Jackie!!

ANYWAY, she just asked me to post this for you all to look at:

http://www.theroot.com/views/was-lincoln-racist?GT1=38002

It's by Henry Louis Gates Jr., a theorist you'll be reading this semester, and it's about Lincoln and his views on race.

Thanks, Jackie!

150 Word Comparison of Freire and Hooks

Comparison & some thoughts

I personally feel that Freire has a very cynical or pessimistic view of education. While I think many times, at least in middle school, there are times when students are required to learn basic rules and concepts that are instilled in all students within one culture, there are many instances when teachers have a profound impact upon students and challenge them to think for themselves. I have always found this to be true in most of the English classes I've had throughout my life, which really encouraged my choice of majoring in English. I also think this goes back to the question of 'why study English?' and the value of English in today's society. I have found it to be the most worthwhile subject in school because I feel that it challenges me to think and form opinions on my own, but also to understand the basic concepts of what it means to be a human and to live, as opposed to finding an area I can succeed in to make a lot of money. In regards to the essays, I was able to relate to hooks in terms of remembering past teachers I've had that really left their mark and encouraged me to be my own person and challenge the norm and question everything I'm presented with. I think this is why education is so valuable, and it would indeed be a shame if, as Freire suggests, it was based entirely on a banking concept of simply receiving and storing information rather than listening and reading and then becoming inspired to do something in the world, as Thoreau often suggests.

Comparison of Freire and hooks

Freire and Hooks in 125 words

Paulo Freire and Bell Hooks state the importance of being taught to rather than projected at when it comes to learning. Freire discusses the situation as a whole using terms such as the “banking” concept where a teacher simply deposits knowledge into the students. Hooks, by contrast, uses her own personal experience as a way to show how it was easier to learn when there was a broader spectrum being exposed. Hooks refers to Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed as a source to back up her ideas for teaching to be a method for liberation to expand learning. Both of them in the course of their essays discuss how education is more than just about general knowledge, but by being a “practice of freedom.” (75)

Hooks and Freire

Monday, February 9, 2009

Friere/Hooks 150 Word Comparison

Friere believes the preferable alternative to this “banking education” teaching style is “problem-posing education,” in which the student is encouraged to think critically and observe the way they exist in and with the world.

Hooks’ solution to the banking education is creating a classroom where the student is essentially forced to find their voice. While her methods for engaging students are a bit intense, Hooks feels that encouraging students to openly talk about feminist views help them to find their voice and learn something about themselves.(144 words)

100-150 Word Comparison (Friere and hooks)

Comparison is exacty 150 words!

Comparison: Friere and hooks

In class tomorrow, Ann Page will give you each a copy of my first essay from last year (yikes!) for you to peruse as you begin your own first essays. This is just to get your thoughts moving and perhaps provide you with some idea of the direction you'd like this paper to take. Your paper does not, however, have to resemble mine even a little; it is simply for you to look at if you wish (and to help demonstrate why you've been forced to write these darned 100 word summaries and comparisons). I make no claim that this is a paper worthy of your admiration; it is simply the one I wrote and am now sharing with you. (Extra points to the first person to identify the error on page 6.)

I'm happy to be a second set of eyes for you as you write your papers, but I should warn you that I will not be within reach via the internet from Thursday afternoon on... so if you want my input before Friday you'll need to contact me by Wednesday night. Good luck with these papers, and have fun! :)

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Revised Summary - Himmelfarb

A Thought on Menand and During (this is more than 100 words and is meant to ask a question, not compare!)

Simon During and Louis Menand seem to agree on one particular idea: The literary studies discipline is a dying breed. During argues that the discipline of English is becoming part of the all-encompassing discipline known as "cultural studies,"and Menand argues that literary studies is becoming less and less of it's own discipline for two reasons. One of these reasons is, in fact, that the humanities disciplines are beginning to merge, but he also points out that specialization and the rise of professionalism has sparked English's demise. Too many professors come from one specific background of literary theory. Everything is subsidized. During would even go on to say that their is no longer enough intellectual conflict to keep literary studies alive and breathing.

Do you think literary studies is become a completely different discipline? Is English dying? Are the humanities dying altogether (not just at Colby-Sawyer!)? What is causing less and less college-bound students to choose English as a course of study?

-Megan R.

Revision of My 100-Word Summary

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Revised Eagleton Summary and Comparison of During and Menand

During’s essay “Teaching Culture” and Menand’s on “The Demise of Disciplinary Authority”, both discuss the role of English academics in a society that flits back and forth between deciding on its worth. While the institution of English remains strong with a solid base stretching back centuries, there is a debate between During’s “knowledge for its own sake” (96) and the academic who becomes a professional based upon need. The authors agree that both courses of action have merit but whether or not society will accept these positions for their intrinsic value has yet to be decided.

A new summary of Himmelfarb and a revised summary of Eagleton...

Terry Eagleton explains how English became an academic course of study in his essay “The Rise of English.” The basis of his argument is that literature replaced religion, to a degree. In Victorian England, there was a spiritual and moral crisis, which led to a heightened sense of the value of literature as experiential and emotional. Studying literature became a way of studying all subjects, most importantly society, history, and spirituality. The original idea that literature made scholars good people was overly idealistic, but the value of literature as an exploration of humanity was recognized then and remains important now.

Revision of 100 Word Summary

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

exactly 100 - ADVOCACY!

Whoops

Monday, February 2, 2009

Response to 100 Word Summaries (thus far)

See you in class.

Casey's 100 Word Summary

Literature replaced religion during the Victorian era and became something to bind society together. It provided English literature with a new lease on life, becoming the thing to study, although it was embraced by the working class before the upper. Scrutiny, a critical journal, was created by the Leavises to analyze all works, previous and current and went so far as to take a political stance that addressed issues of the day. However, the primary concern was what role English literature would take in both society and civilization and what niche it would fill.

100 Word Summary

100 Word Summary of " The New Advocacy and the Old"

100 Word Summary

"The Rise of English" by Terry Eagleton

Terry Eagleton’s essay can be summarized by one of his first sentences that states that “Literature, in the meaning of the word we have inherited, is an ideology” (49). He goes on to say that through the downfall of religion, especially in the Victorian era, literature has excelled, and that the point of literature itself is to “convey timeless truths, thus distracting the masses from their immediate commitments” (51). In this essay, Eagleton also argues for the case of studying “English” as we know it, and why one must read to be a better person, no matter what race, gender, or class.